At this point, we have all seen the videos. Men dressed in plaid shirts, jeans and boots descending on constructions sites, chasing migrants in fields, lurking in courthouse hallways at courthouses, knocking on doors of homes, and surrounding cars. We see them wrestling men and women to the ground. Beating them in some instances. Chasing them. Jumping out of cars and descending. Surrounding unarmed women. Pointing their guns and demanding that people exit their cars. They have shown up at elementary schools demanding to see children of migrants.[i] They purport to be working for the Department of Homeland Security. They are ICE agents, we surmise. But often we don’t know. Because these men, for the most part, display no badges or names.

And they are masked. Their masks are not “government issue” or of the N-95 variety with which we became familiar during COVID. Often these masks are just large, black or green pieces of cloth, or bandanas covering the entire face, save for the eyes. A hat pushed down low also appears to be part of the required uniform.

Despite strong opposition from ordinary Americans to the appearance of a force that many liken to “secret police” in totalitarian regimes, Republican senators have doubled down on ICE agent anonymity, introducing legislation that would make it a felony to release the names of ICE agents.[ii]

There is something particularly menacing about being attacked by faceless people. The mask not only terrorizes the victim of the attack, but it also uniquely empowers the perpetrator. We see this in many of the videos as those who claim to be federal officers, speak crudely and cruelly, and behave with unspeakable brutality against unarmed laborers and their families. The mask prevents their victims from identifying the “officers.” But perhaps the anonymity offered by the mask also encourages these agents to obscure their own humanity from each other and from themselves.

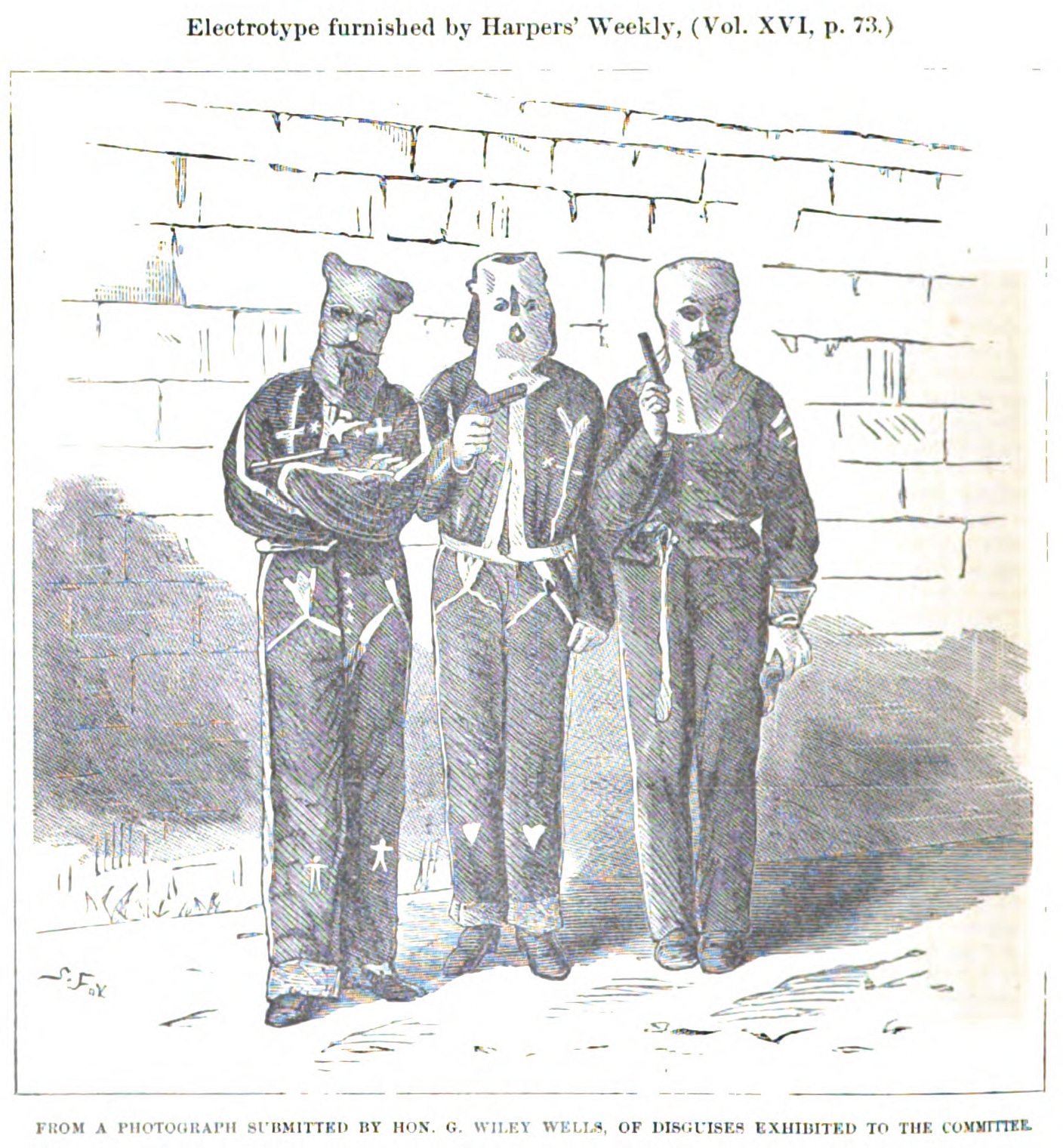

This country has a unique history with the particular terror of masked attackers. The Ku Klux Klan, the violent white supremacist organization terrorized Black people in the American South in the first years after the end of the Civil War and through much of the 20th century. So rampant was Klan violence in the years immediately after the Civil War, that it threatened to derail the promise of the 14th Amendment, which was ratified in 1868 and was designed to ensure that Black people would equal citizens in post-Civil War America.

In the first decade after the end of the Civil War, the violence of the Klan grew to such an alarming level that President Grant encouraged Congress to address the growing problem by passing a statute that would give federal authorities the ability to prosecute those interfering with the constitutional rights of Black people.[iii]

In response Congress enacted the Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871,[iv] which gave the federal government authority to prosecute crimes committed by the Klan. For this reason, the Enforcement Acts are colloquially referred to as the “Ku Klux Klan Acts.” Among its other protections designed to ensure access to voting for Black people, the Enforcement Act of 1870 made it a felony when:

…two or more persons to band or conspire together, or go in disguise upon the public highway, or the premises of another, with intent to ….injure, press, threaten or intimidate any citizen with intent to prevent or hinder his free exercise and enjoyment of any right or privilege granted or secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States.

The reference to disguise was not accidental. Congress held a set of hearings in 1870 and 1871 to receive testimony about the effect of Klan violence in the South.[v] The testimony offered at the hearings was harrowing. Black people courageously stepped forward to tell in their own words what they had endured in towns and hamlets throughout the South. They told of threats, whipping, rape, arson, murder – all carried out by masked and armed bands of men who demanded that Black people do their bidding. Frequently the acts of these mobs were designed to keep Black people from voting, from teaching in newly opened schools, from purchasing land or from demanding to be paid for labor. Whites also testified about how their efforts to assist Black neighbors who faced Klan violence, turned the attention of the mob on them. Local officials were either secretly part of the mobs, or too intimidated to prosecute.

A key feature of these violent mobs – sometimes comprised of five men, sometimes forty - was that they were masked or disguised. Indeed this was a key part of the terror because it spoke to the expectation of impunity. These exchanges from the hearings held in Atlanta, Georgia in 1871 are telling. They mirror similar testimony by countless witnesses in states throughout the South. Thomas Drennon, a blacksmith, and wagon maker in Floyd County was asked about masked men who came to his home late at night:

Question: Have any of them ever come to your house?

Thomas Drennon: Yes sir…. they came there last January, I think….as well as I could count them there were about twenty odd; I could not count them all. They were disguised so that I could not see their faces; they had something over their faces, hanging down.[vi]

Caroline Smith described how she, her husband, and her sister-in-law were stripped and whipped by masked men who warned the women not to “sass any white ladies,” and not to speak of what had happened or who their assailants were. Smith explained,

After they had whipped all three of us Felker looked in and said, “Do you know any of us?’ I said, ‘No I don’t.’ I told them a lie for knew them well enough I knew they would kill me if I said I did.[vii]

CC Hughes testified that in Harelson County masked men came to his house in the middle of the night and beat him brutally. When asked whether he knew the identity of the men, Hughes said he had a sense of whom some of his assailants might be, but “their faces were all covered up….Some of them had sticks in the head-covering so that it would stand up, and some had not, and the covering would hang down behind. They all had their faces covered up with the exception of the holes.”[viii]

In the Enforcement Acts, Congress chose to address the particular outrage of masked assailants who believed that their concealed identity would ensure that they could violate the constitutional rights of freedmen and women with impunity.

Klan violence was briefly stemmed by federal prosecutions brought under the Enforcement Acts until 1875, when the Supreme Court decided in U.S. vs. Cruikshank,[ix] that the 14th Amendment protected only against acts committed by state actors or by those acting under the authority of the state – not mobs or other confederations of violent, masked men. The terror of the Ku Klux Klan came roaring back to power within a few short years and came to dominate southern states for the first half of the 20th century and even in many places into the 1980s. The image of the Klan, and its signature masked group of racist brutes, is seared into the American memory to this day.

And what of the Enforcement Acts? Elements of the Acts’ protections survive in three contemporary civil rights statutes that protect against violations of constitutional rights by state actors. The principal statute can be found at 42 U.S.C. § 1983, known simply as “Section 1983.”[x] This is the statute frequently invoked to sue police officers engaged in racial discrimination and brutality. It is also the civil rights statute that the Supreme Court has severely weakened by its creation of the doctrine of “qualified immunity” which often prevents law enforcement officials from facing personal liability and money damages for their unconstitutional actions. Repeal of that judge-made doctrine was a key feature of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act,[xi] which advocates demanded that Congress to pass in the year after Floyd’s murder. Its passage failed because of the resistance of Republicans in the Senate to repealing qualified immunity.

I reference this history not to say that ICE officers are the same as the masked Klansmen who terrorized Black people for so many decades. I raise this history to remind us of the uniquely repugnant nature of masked assault and violations of civil rights that is such a shameful part of our history. Especially when those wearing masks are targeting members of racial minority groups. This form of racial terror is part of our national DNA. This alone should compel us to resist actions that stir up its memory.

We know that some of the people who have been set upon by ICE officers are U.S. citizens.[xii] These citizens should be able to vindicate their Section 1983 rights. But against whom? Non-citizens also should not be set upon by gangs of men wearing masks. What guarantee do we have that their assailants are in fact ICE agents? Or that they are law enforcement officers of any kind? Has this Administration authorized masked men to terrorize and round-up migrants and U.S. citizens in the name of immigration enforcement? Given the excesses of this Administration, its routine flouting of legal norms and standards, and its zeal to meet self-created detention “quotas,” this may well be within the realm of possibility.

Public service carries with it the responsibility of identification. Anonymity for state officers is not consistent with the requirements of transparency and accountability in a democracy. Many of us still remember the most chilling image of law enforcement during the protests following the murder of George Floyd. It showed a group of masked officers, assembled purportedly to defend the Lincoln Memorial. These masked men wore no name tags or identifying insignia.[xiii] Were they active-duty military? National Guard? Federal corrections officers, as some rumors insisted? The image chills to this day.

Republicans raise concerns about ICE officers being “doxed.”[xiv] But “doxing” has never been understood to include seeing the face or learning the name of a state officer. Measures may be undertaken to protect online access to the home addresses of some federal officers in sensitive roles, as many are advocating for judges who are increasingly living under physical threat because of incendiary rhetoric coming from Trump and his supporters. But concealing their identity is not a constitutional solution.

We have every right to know the identity of those officers are who are abducting migrants and U.S. citizens from our streets, and under whose authority they are purporting to act. Officers of the state should be proud to identify themselves as such. When they are not, it is a warning flag for democracy.

[i] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/los-angeles-schools-leader-explains-why-he-refused-to-let-dhs-agents-see-students

[ii] https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/local/davidson/2025/06/05/blackburn-bill-criminalizing-doxxing-federal-law-enforcement-oconnell-ice/84048878007/

[iii] https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/president-grant-takes-on-the-ku-klux-klan.htm

[iv] https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/EnforcementAct_1870.pdf ; https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/image/EnforcementAct_Feb1871_Page_1.htm; https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/image/EnforcementAct_Apr1871_Page_1.htm .

[v]Published as House Reports and Senate Reports. Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee on the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States. Pts. 1-13. Serial 1529-1541, 1484-1496 (1872).

[vi] Id., Vol. 6, Georgia, at pp. 403.

[vii] Id., at p. 402

[viii] Id., at p. 540.

[ix] U.S. v Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875), https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/92/542

[x] 136. Ku Klux Klan Act, ch. 22, 17 Stat. 13 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§§ 1983, 1985, 1986.

Section 1983 provides that:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress, except that in any action brought against a judicial officer for an act or omission taken in such officer’s judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated or declaratory relief was unavailable. For the purposes of this section, any Act of Congress applicable exclusively to the District of Columbia shall be considered to be a statute of the District of Columbia.

[xi] https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1280

[xiii] https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/the-dystopian-lincoln-memorial-photo-raises-a-grim-question-will-they-protect-us-or-will-they-shoot-us/2020/06/03/7a1c52b4-a5b7-11ea-bb20-ebf0921f3bbd_story.html

[xiv] But the idea that ICE officers are being “doxed tremendously” as some have claimed has yet to be supported by credible evidence. https://www.yahoo.com/news/ice-gets-brutal-fact-check-164342160.html

Superb! Have you or any lawyer brought this as a suit against the Trump administration? Shouldn’t we put this into the hands of NAACP lawyers, or ACLU, or other civil rights attorneys who would take it to court?

Can a mayor or governor order local police to insist that these masked terrorists produce ID and a warrant? Assign them to patrol and intervene?