On Chief Justice Roberts’ 2024 Year-End Report

Challenging Critics & Invoking Heroic Civil Rights-Era Judges To Insulate An Imperial Court

I have been writing about judicial selection, judicial decision-making, and impartiality since 1997 when my first law review article “Judge the Judges” was published in the Boston College Law Review. My attention to these issues reflects my deep and abiding interest in the fairness of our legal system – the system through which I have fought for the rights of those who are most marginalized in our society. There are many inequities in our country and a great deal of unfairness. But ensuring that our legal system is fair has always been my paramount concern, precisely because the law can be such a consequential avenue for the vindication of the rights of those to whom I have devoted my professional career.

During the over 30 years I have worked as a civil rights lawyer, I have asked my clients, and those in the communities I have been privileged to serve to suspend their disbelief and to count on the legal system to protect them and to uphold their rights. They have seen racial discrimination in every aspect of our legal system – from policing to judging. Yet repeatedly I have seen my extraordinary clients suspend cynicism and pessimism and bring their claims of injustice to our courts. My obligation was to represent them to the best of my ability, and to ensure that they had as fair a chance as is possible. Ethically, that has meant to me that I must also fight to promote the fairness of the system itself and the integrity of those who make decisions within that system. I consider this work of the highest order that I owe to my clients and to the students I have taught over decades.

Perhaps that’s why I am so put off and even offended by the implication of Chief Justice Roberts Year-End Report for 2024 https://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/year-end/2024year-endreport.pdf . To be honest I found that I was in agreement with most of the observations he made about the importance of protecting federal judges against violence, against violent rhetoric or even against harsh, intemperate, and unfounded accusations of wrongdoing.

But the implication that underlay the Chief’s essay and that has been stated more explicitly by Justice Alito, and more recently Judge Edith Jones of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, is that critiques of the structure of our judiciary, of judicial opinions, and of judicial conduct, and calls for court reform lead to threats against judges, and imperil the rule of law. And this is frankly unconscionable.

Chief Justice Roberts’ report was, I take it, an effort to more professionally make the case that Judge Edith Jones attempted to make at a recent Federalist Society conference. If you haven’t seen the video, in which Judge Jones set upon Prof. Steve Vladeck, a highly respected and temperate law professor who has become the foremost expert on the Court’s increasing use of its emergency docket, it is worth watching (although it is cringe-inducing). Vladeck is a solid scholar and teacher (at Georgetown Law School) whose work has been acclaimed by scholars across the board. The attention he has brought to legitimate issues involving the Court’s emergency docket has actually resulted in changes in the Court’s practice, as he acknowledges in his book The Shadow Docket.

Judge Jones’ conduct attacking Professor Vladeck on the panel at the Federalist Society Conference was extreme. On a recent episode of his podcast, even conservative scholar Professor William Baude recognized that Judge Jones “did not cover herself in glory” in her poorly argued and thinly supported tirade against Professor Vladeck.

Chief Justice’s Year-End Report takes a sober, temperate, and scholarly approach to the issue. His words are not offensive, and the ideas expressed are not in the main objectionable, at least not to me. We all stand firmly against violence and intimidation of judges. What comes through in the Chief Justice’s message is his tacit acceptance of the association between critiques of the court and threats of violence against judges.

The truth is that much of the criticism of the Court over the past few years has been long overdue. I would argue that many of the court reform suggestions offered by scholars, elected officials and litigators have been beneficial to the public’s understanding of the judicial system, and beneficial to the judicial system itself. Concerns raised by legal scholars and litigation experts about the shadow docket, for example, resulted in changes to how the emergency docket has been handled including the increasing issuance of short opinions explaining the orders in consequential shadow docket cases beginning in 2022. It was the public controversy that flowed from investigative reporting revealing that revealed millions more dollars in gifts had been conferred on at least one Supreme Court justice, that precipitated the submission of amended disclosures by two justices.

The court under the Chief’s leadership issued its own voluntary ethics code in 2023 in response to widespread concern and frank astonishment that the highest court operates without a binding code. https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/Code-of-Conduct-for-Justices_November_13_2023.pdf Justice Amy Coney Barrett had publicly stated her belief that the Court should issue such a code a month prior. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/16/us/politics/supreme-court-ethics-code-amy-coney-barrett.html And at least two justices just in the past six months have publicly endorsed the concept of a congressionally mandated ethics code for the Court, demonstrating that calls for a code that can better ensure ethical accountability by the justices are hardly on the fringe of discourse about the court.https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2024/07/25/supreme-court-kagan-ethics-code-reform/ ; https://www.cnn.com/2024/09/01/politics/ketanji-brown-jackson-scotus-ethics-code/index.html

And clearly in response to the public debate about the black box of Supreme Court recusal practice, at least one justice has begun offering explanations for her recusal in particular cases, a new and clarifying practice that one hopes will catch on. https://www.law.com/nationallawjournal/2023/05/30/2-justices-diverge-on-explaining-reasons-for-recusals/?slreturn=20250102160218

All of this is a far cry from judicial “intimidation” or threats. And none of it is mentioned in the Chief’s report.

It is telling that the context the Chief uses to hammer home his point in this Report is the history of violent threats against judges who were targeted and threatened during the core three decades of early civil rights litigation beginning in the 1950s. It is a clear attempt to push critics back on their heels by “both-sidesing” critiques of conservative judicial practice. The repeated reliance on civil rights history by conservatives as a shield against criticism has become de rigueur (comparing the Court’s Dobbs decision which overruled Roe v Wade to the decision in Brown v Board of Education overruling Plessy v. Ferguson is among the most odious examples of this cynical rhetorical tactic). But the knowledge of that history is often too slim to bear the weight of the point they seek to make.

Chief Justice Roberts’ Report includes a photograph of a cross burned outside the apartment building of Chief Justice Earl Warren who led the Court in issuing the decision Brown v. Board of Education and many other subsequent landmark civil rights cases. Roberts also refers extensively to South Carolina federal district court Judge Waties Waring, who became a champion to civil rights lawyers and great friend of Thurgood Marshall in the 1940s and 50s.

A eighth generation Charlestonian and descendant of a confederate soldier, Waring left South Carolina soon after his decision in the South Carolina challenge to segregation in the consolidated Brown cases. His departure was occasioned not only by threats of violence (including a bomb thrown at his home), but also because he and his wife were rendered social nullities by the upper-class society of which he had always been a part, which ostracized them because of his decisions in civil rights cases. The Chief’s Year-End Report includes a photograph of the frontage of the federal district court in Charleston, which was renamed to honor Judge Waring in 2015. I was honored to speak at the renaming ceremony.

Judge Edith Jones also referred to civil rights history during her effort at the Federalist Society Conference to discredit the analysis of Prof. Vladeck, who has written extensively about the one-judge district courts which have resulted in conservative lawyers to “judge shop” their cases to one judge, Matthew Kacsmaryk in the northern district of Texas, a reliably conservative judge who has routinely issued favorable rulings in cases from abortion rights to powers exercised by President Biden to forgive student loans. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/05/opinion/republicans-judges-biden.html In what she apparently thought was a killer riposte, Judge Jones at one point bellowed “what about Judge Justice?” She was of course referring to Judge William Wayne Justice, a federal district court in the eastern district of Texas who was the favorite of civil rights lawyers during the 1960s, 70s and early 80s. As a trial judge he courageously decided cases like Plyer v. Doe, which established the right of undocumented children to access public education, and decided school desegregation cases enforcing Brown in Texas. Judge Justice was asked in 2006 about the effect of his decision-making on his life. This passage from the interview is illuminating.

After the decision forced local high school Robert E. Lee to jettison its Confederate band uniforms and rebel flags, the phone started ringing and the hate mail started coming. Bumper stickers were printed that read “Will Rogers never met Judge Justice.” Carpenters working on his house walked off the job when they found out who owned it, and his wife, Sue, was refused service by local beauticians. “Our social life dwindled,” the judge says in his easy drawl. “But you know, I’d taken an oath to defend and protect the Constitution, and I was going to do my best.” https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/william-wayne-justice/

That Waring and Justice were cut off by the society in which they had been respected leaders as a result of their decision-making, explains why we regard Waring and Justice as “courageous.” Those southern judges who followed the law, applied Brown, and ruled in favor of civil rights claimants did so despite the threats of violence, and also in the face of scorn and opprobrium from their colleagues, friends, and neighbors. During those years, judges like Waring and Justice were exceedingly rare in the south.

What made civil rights claimants seek out Judge Justice and Judge Waring was the opportunity to receive a fair hearing. It wasn’t that these judges guaranteed a favorable outcome, it was that so many other federal district judges in the south guaranteed an unfair hearing. Thurgood Marshall famously said that when he tried his first case before Judge Waring in South Carolina (a teacher pay case), it was the first time in a southern court that Marshall was able to actually try his case – make his full arguments, put on his witnesses and present all his evidence. He said he spent most of the trial with “my mouth hanging open half the time” in astonishment.

The issue wasn’t that Judge Waring or Judge Justice became champions in the eyes of civil rights litigators. It was that so many other judges abused the system by not giving lawyers litigating civil rights claims a fair opportunity to try their cases, or by allowing local districts to openly defy the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown. For every Judge Justice or Judge Waring, there were many more like Judge Harold Cox, who was described by pioneering civil rights litigator and later federal district judge Constance Baker Motley as “the most openly racist judge ever to sit on the federal court bench.” Or Judge Sidney Mize, whose conduct and rulings in the case challenging the exclusion of Black applicant James Meredith from admission to the University of Mississippi defy credulity. Far too often Judges like Waring and Justice were the only judges where civil rights claimants could receive a fair hearing.

Civil rights lawyers were perpetually foiled by judges who were openly prejudiced or who simply refused to compel southern jurisdictions to comply with the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown. And when they filed cases before Judge Justice or Judge Waring, the claims were matters related directly to the forum where those judges sat. This is not what is happening today with judge shopping cases in the northern district of Texas. That is why the history of Judges Justice and Waring cannot justify the decision by conservative lawyers to repeatedly file cases before one extremely conservative district court judge, even when their claims bear no relationship to the forum in Texas where that judge sits.

The Chief closed his report with a point that demanded greater narrative attention. Indeed I regard it as the most important passage in the essay: “[t]he federal courts must do their part to preserve the public’s confidence in our institutions.” Yes. There’s the rub. What of the responsibility of courts to earn and maintain the public’s confidence?

The Chief might have acknowledged – however briefly - that some critiques of the Supreme Court’s practices have actually led to positive changes. And he might have stated his intention in the New Year to encourage his fellow colleagues and judges across the federal system to redouble their efforts to ensure that their conduct promotes the public’s confidence in the judicial system (timely and thorough financial disclosure reporting might be a start). Such a statement at the end of his essay would have done more to improve the federal courts’ standing with the public, than the repeated and heated denials from judges whose conduct has garnered scrutiny.

Judges are not kings. So long as we live in a democracy, judges – including Supreme Court justices – do their work within our democracy. Not above it. For this reason, I do not intend to stop writing and speaking responsibly and as temperately as I’m able, about issues of judicial decision-making and process, and about reforms that can strengthen the public’s confidence in the integrity of our justice system.

###

Additional Sources:

Stephen Vladeck, The Shadow Docket: How the Supreme Court Uses Stealth Rulings to Amass Power and Undermine the Republic (Basic Books 2023)

Tinsley E. Yarborough, A Passion for Justice: J. Waties Waring and Civil Rights (Oxford University Press, 2001)

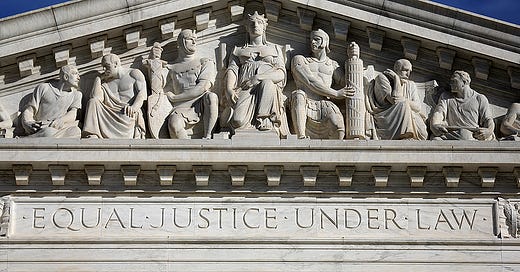

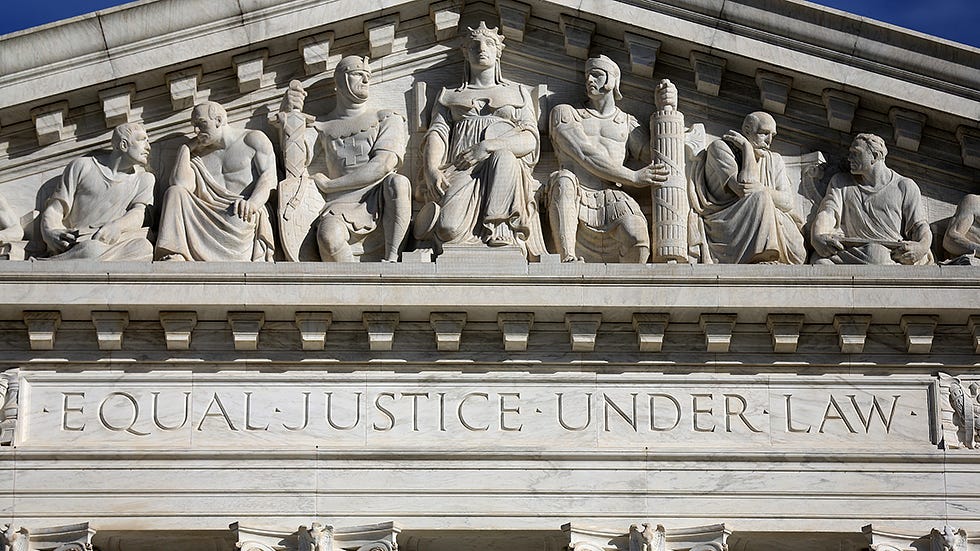

Constance Baker Motley, Equal Justice Under Law: An Autobiography by Constance Baker Motley (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1998).

Thank you for this excellent and objective critique. When reading Justice Robert's comments, I was struck by the defensive tenor of his remarks. He has an obligation to the institution, as well as all of us, to speak to the betterment of the Court. His defensiveness achieves the opposite.

Me thinks he does protest too much - really telling.